#25: Finding the ‘Positive’ Climate Story Through Photo Activism

Greenpeace’s former Head of Photography reflects on why fun and positivity are key for successful campaigns – even, or especially, in China.

In our first issue of 2025, award-winning photographer and visual storyteller John Novis shares a deeply personal experience from the spring of 2007. As part of an international team, he went on an expedition to the northern side of Qomolangma (Mount Everest) to document the heart-wrenching reality of glacial retreat on the “Third Pole.” The Hindu Kush Himalaya Region, also known as“Asia’s Water Tower,” is critical to billions in China and South Asia, and is experiencing some of the fastest and most profound impacts of climate change.

During his 26 years with Greenpeace International, John used documentary photography to raise public awareness of many environmental crises, including climate change. His takeaway? “Fun” and “positivity” are not just essential when you’re hiking through an icy mountain landscape, but also for reaching a wider audience and forging change.

This may sound counterintuitive, even troubling to some. After all, what’s fun and positive about climate change? But I know he is not attempting to sugarcoat disasters or to obsessively draw a “silver lining” on our planetary crisis.

It is true that we’re sleepwalking toward a future where global temperatures could rise by 3°C – a prospect that feels anything but positive. Yet, in moments of despair, we – as human beings – instinctively look for hope, because hope gives us the courage to connect, to create, and to envision a way forward.

John’s insights carry particular weight in the context of China, and they resonate with me so much. “Even” because today, most climate NGOs and think tanks in China primarily focus on influencing government policy. The landscape has become increasingly dry and technical, with a noticeable lack of inspiring, uplifting stories. This has led to a growing sense of fatigue, frustration, and disempowerment among climate advocates. “Especially” because we know from experience that negative narratives tend to have a shorter lifespan in China. A “positive” climate story, he argues, can inspire action, build momentum, and foster the collective belief that change is possible.

As we were editing this essay, two events took place on the Tibetan Plateau.

Two days ago, a 6.8 magnitude earthquake struck Dingri County in Shigatse Prefecture, less than 60 kilometers from Mount Qomolangma Base Camp. The very next day, nearly 1,000 kilometers away, another 5.5-magnitude earthquake shook Maduo County in Qinghai’s Golog Prefecture, where the Yellow River originates. The two earthquakes were “unrelated,” according to Chinese experts from the National Earthquake Networks Center.

And just two weeks ago, the Chinese government approved a massive hydropower project on the lower reaches of the Yarlung Tsangpo River. Designed to generate over three times more power than the Three Gorges Dam, the world’s next largest hydropower project – also the most expensive infrastructure – has been hailed as a milestone in China’s “dual carbon” goals and its efforts to combat climate change. Officials assured that the project “would not harm” downstream regions such as India and Bangladesh.

Despite the government’s assurances, some geological experts and environmental advocates see the project as a gamble. Over the past decade, many argue that preserving the region’s unparalleled biodiversity through national parks is a safer and more sustainable alternative to exploiting its hydropower potential.

We will delve deeper into the role of mega-hydropower projects in China’s “dual carbon” transition in a future newsletter. In the meantime, I wish you a belated Happy New Year, and I hope you enjoy the breathtaking photographs.

John Novis: Finding the ‘Positive’ Climate Story Through ‘Photo Activism’

Greenpeace’s former Head of Photography reflects on why fun and positivity are key for successful campaigns – especially in China.

By John Novis

Edited by Hongqiao Liu and Kevin Schoenmakers

In 1997, I was part of a Greenpeace campaign to record the polar regions’ rapid loss of ice. At that time, man-made climate change was already the scientific consensus but was still far from widely accepted as alarming, urgent, or even as true. My goal was to repeat the success of an earlier expedition, during which we took photos that helped pressure nations to sign a treaty to protect Antarctica.

However, the photos we returned home with this time, after our long journey on the Arctic Sunrise ship, mostly showed stark landscapes. They lacked impacted people, flora, and fauna that would resonate with the public, let alone convey the urgent consequences of climate breakdown to governments, industries, or investors.

In search of more immediate visuals, we turned our focus to China. The Himalayas and the countless snow peaks on the Tibetan Plateau, known as the “Third Pole,” are home to the largest ice mass outside the polar regions. The area experiences climate change at a faster pace than anywhere else on the planet, affecting local communities, wildlife, and the mountain range’s many glaciers.

In the spring of 2007, after a 10-day expedition, we – an international team of scientists, photojournalists, and environmental advocates – arrived at the Rongbuk Glacier on the northern side of Qomolangma (Mount Everest) to document its retreat. Earlier expeditions and the Chinese Academy of Science had been monitoring the shrinkage of the glacier – one of the largest in the Himalayas – over a number of years.

Support Shuang Tan

Shuang Tan is an independent initiative dedicated to tracking China’s energy transition and decarbonization. The newsletter is curated, written, and edited by Hongqiao Liu, with additional editing by Kevin Schoenmakers.

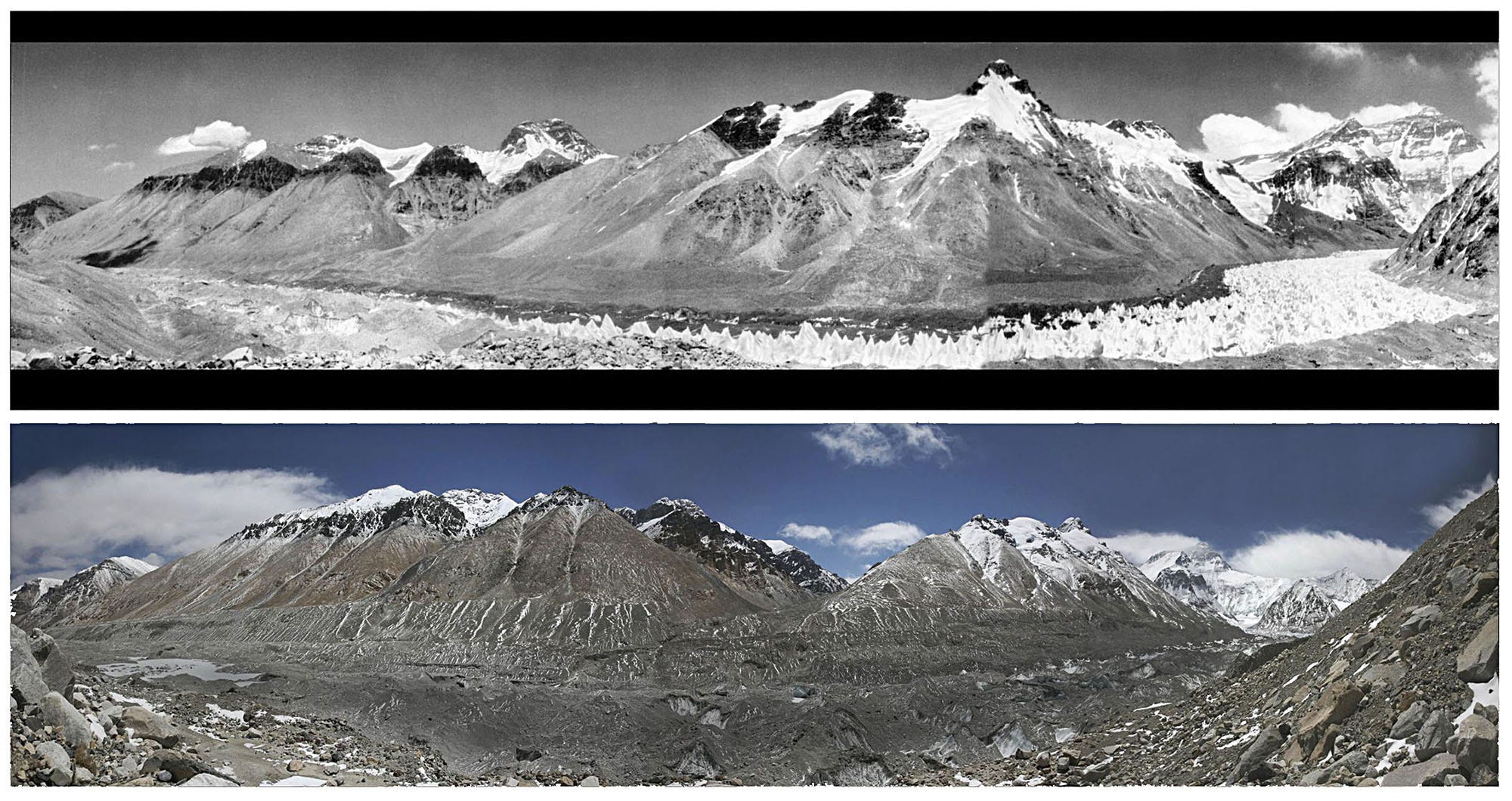

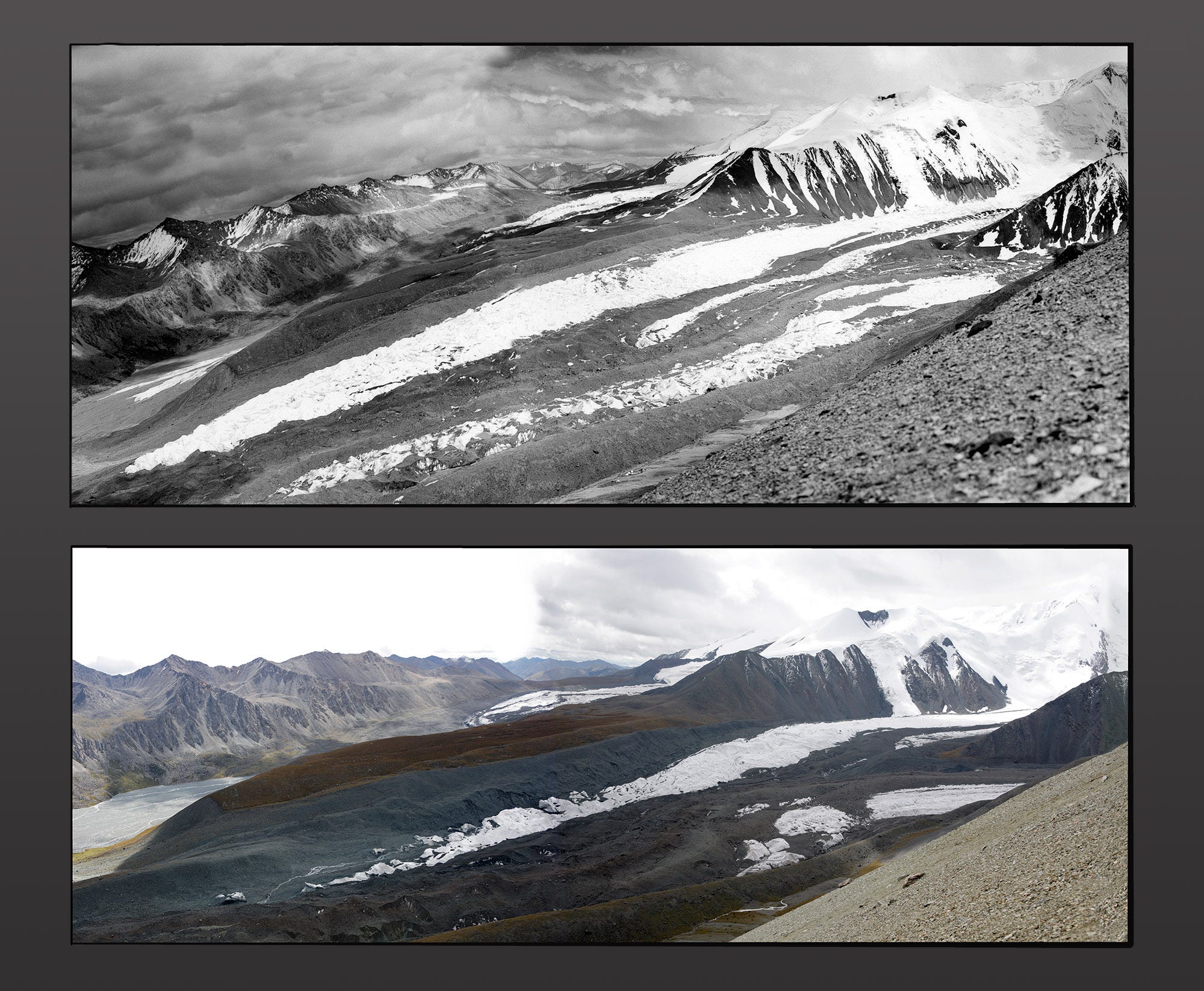

Greenpeace colleagues in the Beijing office had gained permission from China Science Press to use a 1968 panoramic photo showing the western side of the iconic glacier. It lies along the route mountaineers take to the peak, and as such features in many images and stories of those who have braved the conquest.

Our team set out walking across the glacier to reach the viewpoint of the 1968 photo. But after about half a day, our Tibetan guide halted the walk as crevasses had begun appearing. He feared for our safety. I was devastated that, after months of training and preparation for this singular endeavor, we could see our destination about a kilometer away but could advance no further. I started photographing from where we had stopped, the view being not exactly as in 1968 but close enough to give a visual comparison.

The Rongbuk Glacier was astonishing. A huge expanse of moraine, the dark sediment left by a glacier, filled the frame instead of the white ice that was abundant in the 1968 photo. It left me no doubt that rapid change was happening to the mountain. After carefully comparing the old and new photos, we concluded that the glacier had retreated by two kilometers over the preceding four decades.

The science seemed evident before our eyes: climate change disrupts the Himalayas’ water cycle. Moisture is carried from the ocean and falls as rain or snow on the mountains. Much of it seeps into the ground, with the mountains acting as gigantic sponges. The rest is stored as ice and melts slowly in summer. But rain is becoming more erratic, either coming in torrents or not at all. Such abnormal rainfall patterns can significantly contribute to groundwater depletion and, as a result, glacier shrinkage.

During the expedition, I also took photos of how the changing weather patterns affected local people and wildlife. At the time of the expedition to the Rongbuk Glacier, I didn’t fully grasp the far-reaching consequences of climate change. Looking back now, it is evident that the plight of Tibetan nomadic communities foreshadowed a much larger issue: climate refugees. All around the world, millions of people have been forced to flee their homes and seek survival in regions less impacted by climate change. This mass displacement poses immense risks to health, security, and economic stability, with potentially catastrophic consequences.

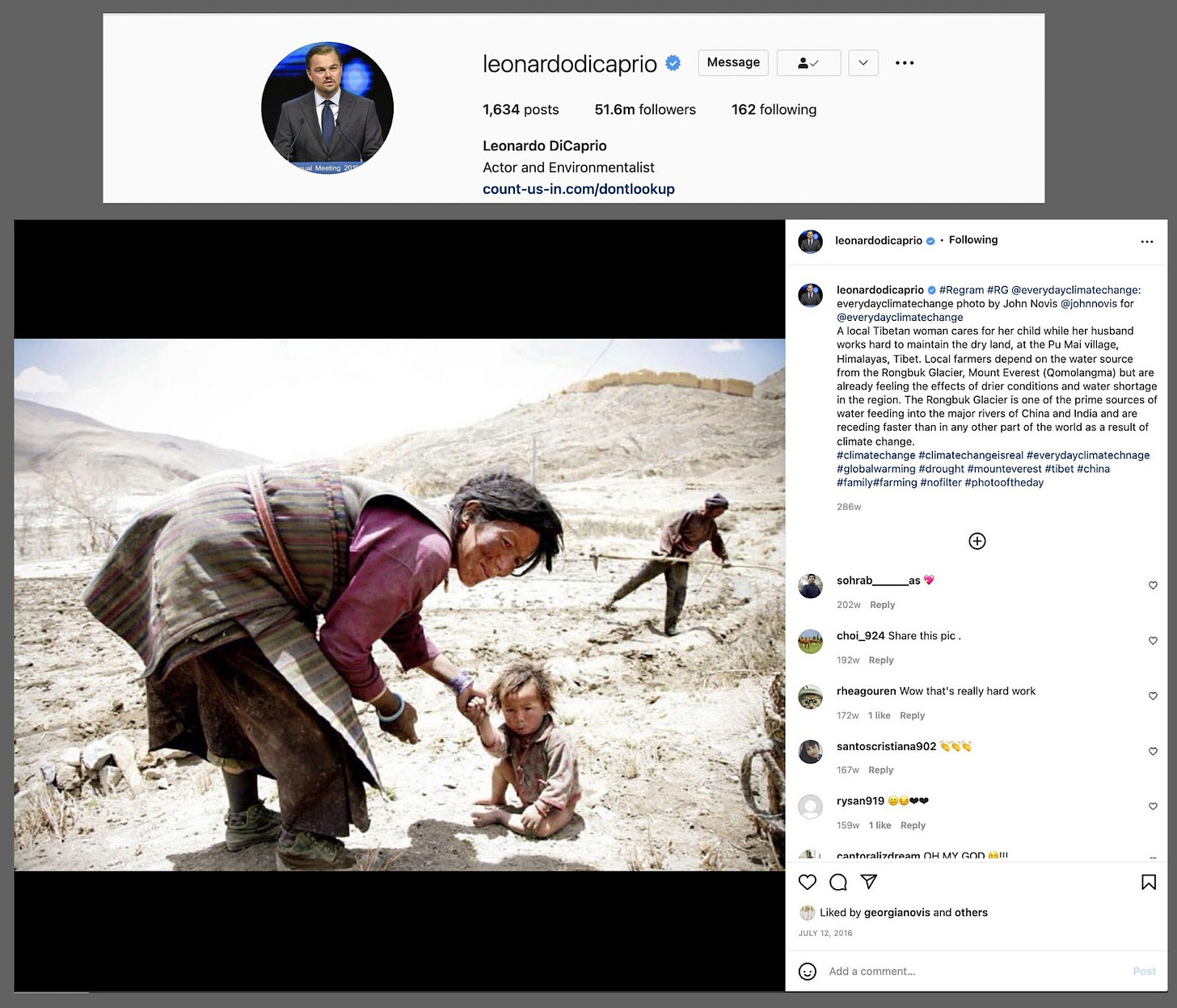

I had asked a Beijing-based environmental journalist to accompany the team to help make sure our journey would receive Chinese and international press coverage. Several magazines, including Marie Claire and Asia Geographic, published our photos and wrote accompanying features with titles such as “Mount Everest is Melting.” Leonardo DiCaprio shared a photo of a farmer and child in dryland conditions near Mount Qomolangma to his millions of social media followers. Greenpeace used the imagery in its fundraising, and I have used it in talks to demonstrate the difficulties of visualizing climate change.

During my 26-year tenure with Greenpeace, I documented all kinds of issues, from deforestation to illegal fishing, and, in China, grassland degradation, desertification, and water pollution. I witnessed how the organization’s photo assignments and edited imagery could change public perception and trigger debate about our relationship with the environment.

Over time, I gradually realized the clear distinction between the photo stories created at Greenpeace – what I call “photo activism” – and those produced in traditional photojournalism. While there is no difference in terms of quality, the images have different destinations. Our photos don’t just appear in news and magazine publications. We actively pushed for them to be used in press handouts, exhibitions, books, seminars, press conferences, fundraising events, and traditional and social media.

For photo activism to be effective, it is essential to document both the damage that is done and the beauty that is possible. For example, juxtaposing images of whales swimming freely or playful baby seals with scenes of their slaughter creates a striking aesthetic contrast, much like showcasing the grandeur of an ancient forest alongside the devastation of a clear-cut plot. Emphasizing positivity inspires hope, reminds viewers of what remains worth protecting, and encourages them to take action, instead of leading to indifference and thoughts like, “Why bother? It’s all messed up anyway.”

Now in retirement, I still remain an optimist about mankind’s climate change challenge. Perhaps my optimism stems from being young in the ‘60s and ‘70s, when changing ideas made an enlightened world seem possible. At the same time, I now see how hard it is for my daughters and grandchildren, who have never known a world without climate change, to keep spirits high.

But I believe photo activism continues to be a powerful tool for creating debate and evoking action, perhaps more so than ever. Technology and media have radically shifted since our expeditions in the 2000s. Climate pressure groups and citizen journalists armed with smartphones and social media capture and share every extreme weather event and climate protest. Even in less open societies such as China or Russia, I believe such imagery will find its way past internet controls and have people demanding action.

More recently, as our already saturated information landscape has seen the arrival of AI-generated images meant to disinform, people’s first response to a photo is not to consider its content but to question its credibility. However, I could see AI-generated photo activism appealing to a new generation and enhancing the climate debate.

Another source of optimism, for me, is how climate change protests were almost exclusively organized by NGO protest groups back in the 2000s, yet today young people are expressing their concerns on a grassroots level and organizing protests through social media. I documented one Fridays for Future demonstration through a participant’s eyes, from making banners in her family living room with school friends to marching and finishing the day at a rally with a national politician making an impassioned speech.

And I believe optimism is the driving force behind any successful campaign. As long as a team maintains their vision and group spirit despite disagreement and infuriating obstacles, optimism will surface the “fun” elements of the action even in the darkest moments. If we were all pessimists, nothing would happen at all!

Get in touch

I hope you enjoy this newsletter. Share your thoughts in the comments.

If you’d like to write for Shuang Tan, republish our articles, or submit a testimonial, email us at contact@shuangtan.me.

Until next week,

Hongqiao