#20: Carbon Pricing, Chinese Aviation’s Inevitable Destination

Facing the dual pressures of integrating national and international carbon pricing programs, China's aviation industry must start acting now.

For this week’s newsletter, I worked with Yingzhi Sarah Tang, a Senior Research Associate at the Toronto-based Institute for Sustainable Finance, to explore how upcoming carbon pricing schemes will impact China’s aviation sector.

Yingzhi worked with both the private and public sectors in Europe, Asia, and North America to accelerate their climate and biodiversity ambitions, and previously served as the Deputy Director of the Green BRI Center at the Beijing-based International Institute of Green Finance, an internationally renowned Chinese think tank on sustainable finance.

In this article, Yingzhi offers a clear and insightful analysis of two market-based mechanisms that will impose a carbon price on both domestic and international aviation activities: China’s national Emissions Trading System (ETS) for domestic aviation, and the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) for international flights, which are not covered by the Paris Agreement.

While aviation’s absolute emissions appear almost negligible compared to other hard-to-abate sectors such as coal power, steel, and aluminum, the sector faces unique challenges. Decarbonization technologies are complex to develop and costly to deploy while the growing demand for air travel drives emissions to soar. This explains why, at the very beginning of the conception of a national ETS, China’s state planner National Development and Reform Commission identified aviation as one of the eight key industries to be included in the new carbon market.

Will the two carbon pricing schemes accelerate the decarbonization of China’s aviation sector? There is some positive evidence. As Yingzhi writes, pre-pandemic data from Guangzhou’s ETS pilot showed emissions declined despite rising activity levels.

However, as with all carbon pricing mechanisms, the devil is in the details. (In case you missed it: Simon Göß wrote an excellent reflection on carboneer’s experience of helping 30+ Chinese suppliers comply with the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism.)

Implementing complex market-based regulations requires accurate emissions tracking, which can only be built on aviation companies’ enhanced carbon management capacities. To demonstrate genuine decarbonization efforts, they must also develop Paris-aligned transition plans, which, for now, are absent.

Moreover, truthful compliance, particularly with CORSIA, would require an entire support ecosystem. At a minimum, this means having capable carbon accounting service providers, adequate suppliers of high-quality carbon credits that uphold environmental and social integrity, and third-party certificate authorities that shield companies from fraud and greenwashing.

Additionally, achieving deeper decarbonization in aviation will require increased investment in low-carbon technologies from both government and industry. While it may sound like a familiar refrain, many are pinning their hopes on Sustainable Aviation Fuels (SAF) and China’s well-tested ability to scale up production.

The more important question is, as one of the world’s largest aviation emitters, can China drive the global efforts to reduce global aviation emissions?

I hope you enjoy this newsletter. Have a different perspective? Share your thoughts in the comments. If you’d like to write for Shuang Tan, republish our articles, or submit a testimonial, email us at contact@shuangtan.me.

Until next week,

Hongqiao

Carbon Pricing, Chinese Aviation’s Inevitable Destination

Facing the dual pressures of integrating national and international carbon pricing programs, China's aviation industry must start acting now.

China is committed to carbon peaking by 2030. But with the country’s domestic and international travel forecast to increase, one sector is set to fly right past that deadline: aviation.

Flying is energy-intensive yet hard to decarbonize. The most promising solution in the near term – replacing petroleum-based jet fuels with Sustainable Aviation Fuels (SAF) – faces cost and production constraints. Other abatement options, such as hydrogen and electric aircraft, are still in early development.

Today, the sector accounts for less than 1% of China’s total emissions.1 But emissions are set to grow given the country’s strong demand for air travel. The International Energy Agency has cautioned the country to “reconcile its ambition of developing its aviation industry with its climate policies.”

China’s aviation sector will soon need to comply with two carbon pricing mechanisms: the China national carbon market, where their domestic aviation activities will be regulated alongside high-emitting coal power, and the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA), in which they must offset their emissions from international flights.

How will the two carbon pricing schemes impact the Chinese aviation sector? Can they accelerate sustainable aviation development and help China achieve its climate goals?

Domestic regime: China’s National ETS

Despite a negligible share, the aviation sector has been a focus of Beijing’s decarbonization agenda. It was one of eight sectors the National Development and Reform Commission, the state planner, decided to include in China’s national carbon emission trading scheme (ETS), alongside other notorious polluting sectors like coal power, steelmaking, and cement.

China’s ETS launched covering only the power sector. But as the carbon market celebrates its third anniversary, government and market stakeholders are accelerating the preparation for aviation’s inclusion.

Entering China’s national ETS could be a game changer for the aviation sector, pushing it to improve fuel efficiency while scaling up the adoption of low-carbon fuels.

Simply put, an ETS puts a price on carbon emissions and, therefore, incentivizes polluters to reduce emissions over time. The market-based mechanism allows abatement to happen where it is most cost-effective. Depending on the rulebook, entering the national ETS will bring down the aviation sector’s emission intensity, absolute emissions, or both.

Being part of an ETS will also shift the aviation sector’s approach to climate mitigation from buying carbon credits to voluntarily offset emissions, a gesture to show social responsibility, to prioritizing substantial emission reduction in its activities, an obligation to meet compliance constraints and manage carbon risks.

The EU ETS has successfully demonstrated such an impact. Since 2012, the carbon pricing scheme has led to 17 million tonnes of annual emission reduction from aviation activities within the European Economic Area (EEA), a drop of around 11%. As the EU ETS gradually phases out free allocation and transitions to full auctioning from 2026 onward, it will create even stronger incentives for the EU’s aviation sector to reduce their emissions.

Inside China, three ETS pilots in Guangdong, Shanghai, and Tianjin that cover the aviation sector have also delivered similar effects.

(To explore different carbon pricing mechanisms, China permitted eight regional pilots before officially introducing the national carbon market. Destined to be integrated into the national ETS, the regional pilots are currently running in parallel with the national market.)

For instance, the Guangdong pilot, which has covered domestic aviation since 2016, now includes four airlines, including China’s biggest – China Southern. Pre-pandemic data shows the covered airlines saw a 3.1% year-on-year emission reduction in 2018.

International regime: CORSIA

While the timeline for entering the China national ETS remains unclear, it is certain that, starting in 2027, Chinese airlines will have to comply with another carbon pricing scheme – Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA), an initiative of the UN agency International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO).

Introduced in 2016, CORSIA is the world’s first regulatory, market-based mechanism specific to international aviation, an activity neglected by the Paris Agreement.

As China has gone global, Chinese airlines have emerged as major emitters in international aviation. Between 2015 and 2019, their aggregate emissions from international flights ranked third globally – although only reaching 40% of the levels of the United States.

Aspiring to foster sustainable growth in global civil aviation, the ICAO introduced a target in 2019, urging its member states to “achieve carbon-neutral growth from 2020 onwards.”

China, an ICAO member state, openly opposed the target, arguing it “goes at the expense of the legitimate rights to the development of developing countries and emerging market countries.”

CORSIA tackles airlines’ residual CO2 emissions after they have implemented various abatement measures, such as fuel efficiency improvements and SAF substitutions.2 Under CORSIA, airlines use eligible carbon credits, or “emissions units,” to offset any CO2 emissions above the baseline from international flights.

In practice, covered airlines must offset a given percentage of their CO2 emissions from international flights every year. From 2021 to 2032, this percentage only reflects the international aviation sector’s global average growth of emissions in a given year, known as the sector’s growth factor. From 2033 to 2035, an airline’s individual growth factor will determine 15% of its offsetting requirement.3

ICAO’s figure below illustrates how this percentage is calculated:

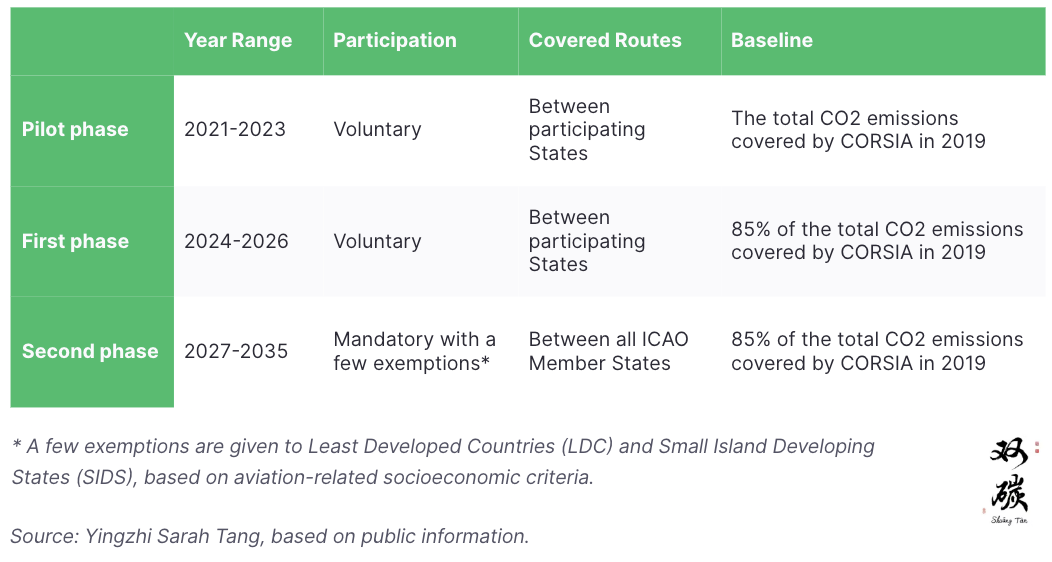

CORSIA is implemented in three phases:

China did not volunteer to participate in CORSIA’s Pilot Phase and First Phase. The Second Phase, however, is mandatory for all ICAO member states, including China.

Complying with CORSIA’s provisions would require major Chinese airlines to balance growing their international aviation while delivering long-term climate targets.

But with less than three years remaining before CORSIA enters the Second Phase, it is unclear how prepared Chinese airlines are. Even the “big three” – China Southern, China Eastern, and Air China – have yet to announce any public plans besides acknowledging that they are aware and will comply.

To ensure transparency, the ICAO introduced a mandatory Measurement, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) policy in 2018. Except for a few exemptions, all airlines had to start submitting their CO2 emissions from international flights in 2019, regardless of their current participation status. This should mean Chinese airlines have been submitting their emissions from international flights to ICAO for the past five years.

In 2018, CAAC, the Chinese regulator, introduced an interim measure on MRV, followed by a guide and a template in 2020. CAAC asks airlines to submit an annual CO2 emission report, which also covers their annual consumption of SAF. Chinese airlines supposedly comply with CAAC rules. Interestingly, this MRV requirement lays some groundwork for China’s national ETS.

While CORSIA poses a new compliance challenge to Chinese airlines, it also creates some opportunities for China’s carbon offset market. During the Pilot Phase, ICAO recognized certain carbon credits from China’s voluntary emission reduction scheme – China Certified Emission Reductions (CCERs).

However, CCERs are not included in the list of eligible credits for the First Phase. Should CCERs become eligible again – which is likely following the relaunch of CCERs in 2024 – the new international carbon offsetting scheme could attract international capital to support carbon reduction and removal activities inside China.

The Path Forward

The inevitable domestic and international carbon pricing regimes pressure the aviation sector in China to rethink its growth trajectory. For this hard-to-abate sector, it is a delicate balance between growing aviation activities, which stimulate the economy, and achieving carbon neutrality.

Due to the hard-to-abate nature of their activities, airlines typically purchase offsets from voluntary carbon markets as compensation rather than directly reducing their own emissions. The lack of fungibility – “a tonne is a tonne is a tonne” – in carbon offsets and oversight in the voluntary carbon markets have led to inconsistencies and fraud.

Despite the controversies surrounding fraudulent practices and greenwashing allegations, offsetting remains a valid approach to compensate for emissions that cannot be cost-effectively abated with current technologies.

However, as a safeguard measure to limit the worst impacts of climate change, offsetting must come at the last of the mitigation hierarchy. In other words, companies must prioritize measures that avoid and mitigate their climate impacts along their value chain over offsetting. Many sustainability standards bodies, such as the Carbon Disclosure Project and the Science-Based Targets Initiative, have adopted this principle.

To prepare for the regimes, multiple stakeholders can act now.

A robust MRV system is paramount to the success of both regimes. Regulators such as CAAC should periodically review and update the 2020 MRV guide and template, borrowing the latest good practices cited by ICAO and implemented in other jurisdictions such as the EU. To enhance transparency, CAAC and Chinese airlines can also launch a public and accessible emission data tracker.

Improving fuel efficiency and exploring the use of SAF, as mentioned in CAAC’s 14th Five-Year Green Development Plan, are immediate steps airlines can take. In its latest Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), the Chinese government commits to support R&D of low-carbon aviation fuels. In China’s next NDC update, forthcoming in 2025, a quantitative target such as mandating SAF to be above a certain threshold in aviation fuel blend would catalyze more supply and demand.

A few Chinese biofuel companies are planning to trial SAF production. Government subsidies, similar to the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in the U.S. (which has approximately $3.3 billion in tax credits for SAF), will help SAF production to take off. Airlines can also commit long-term purchase agreements to provide market certainty.

In the long run, technologies will play a critical role in accelerating the low-carbon transition in aviation. For example, channeling public and private investment into R&D of new generations of low-carbon aircraft and advanced battery systems could unlock new emission reductions.

With the Second Phase on the horizon, Chinese airlines should start looking into the CORSIA-eligible crediting programs and methodologies to prepare for compliance.

In principle, they should only purchase high-quality offsets from credible projects such as those with Core Carbon Principles labeling. They should also consider prioritizing offsetting projects inside China, such as afforestation, clean energy, and waste management projects to bolster climate and nature actions closer to home.

Support Shuang Tan

Shuang Tan is an independent initiative dedicated to tracking China’s energy transition and decarbonization. The newsletter is curated, written, and edited by Hongqiao Liu.

Enjoy what you are reading? Pledge a subscription to show support.

Get in touch

We will soon start accepting submissions. Stay tuned for our pitch guide!

For feedback, inquiries, and funding opportunities, please write to contact@shuangtan.me.

According to the latest data (2022) from ClimateTrace, a global coalition to track and report GHG emissions, transportation accounted for 6.04% of China’s total GHG emissions in 2022. Under transportation, domestic aviation represents 7.89% of transportation emissions; international aviation represented 1.24%. In total, domestic and international aviation emissions combined took up 0.55% of China’s total emissions in 2022.

From 2021 onwards, airlines can reduce their CORSIA offsetting requirements by claiming emissions reductions from CORSIA Eligible Fuels, including sustainable aviation and lower carbon fuels that meet CORSIA’s criteria. However, these alternative fuels have yet to be produced or used at scale.

Calculated as: (individual airline’s emissions in the given compliance year - its baseline emissions)/ individual airline’s emissions in the given compliance year